Electrospinning a medicinal Kleenex

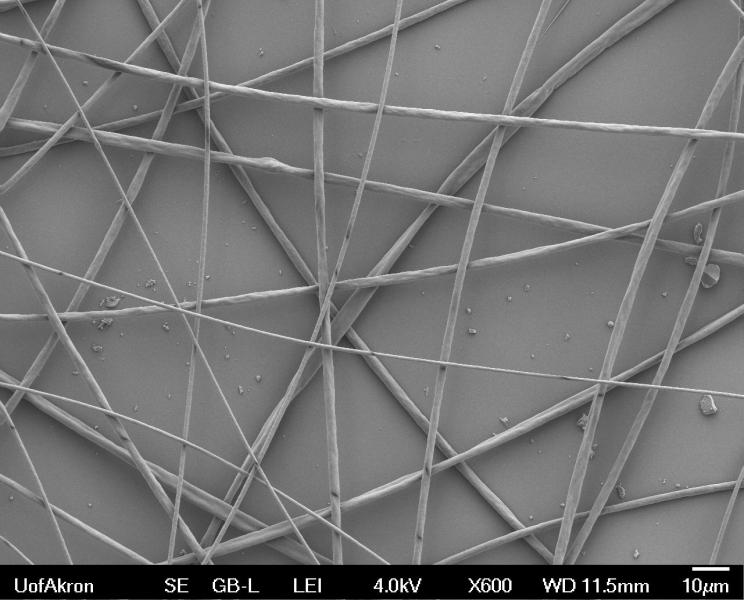

Dr. Darrell Reneker waves his hand beneath a glowing cascade swirling from a narrow nozzle. Light glints off coils of the nanofibers produced in his sun-drenched lab on the top floor of the University of Akron’s polymer science center. He gathers strands of a translucent filament as it coils through the air, finer than spider silk.

Electropsinning is a process Reneker has been refining for decades.

Reneker says the technique is, "so simple and you can make fibers of all kinds of materials and with tiny quantities of materials and we can spin those into fibers just as simple as you saw me spinning this stuff.”

Although the process is not new -- it’s been for years used to make fiber filters -- Reneker is guiding a new use for electrospinning technology.

He is helping the team develop what he calls, "little chemical factories in a Kleenex.”

The new polymer trio

At a spry 82, Reneker is part of a multidisciplinary team working on a new generation of wound-healing materials. He’s using electrospinning to develop self-absorbing bandages.

The second member, Matt Becker, teaches chemistry and is head of the Center for Biomaterials in Medicine at the Austen Bioinnovation Institute in Akron.

His speciality is developing enhancements for degradable bandages that aid tissue generation. Becker achieves this by using bio-compatible building blocks.

He says most of his polymers are amino-acid based, so your body absorbs the compounds as part of normal metabolism. He says most of his polymers are amino-acid based, so your body absorbs the compounds as part of normal metabolism.

The most recent breakthrough, though, comes from the youngest member of the trio, graduate student Jukuan Zheng, who holds a vial of white granules.

Click chemistry holds the key

Jukuan’s mystery molecule allows for one-step customization of the degradable bandage through a novel process called “click chemistry.”

Like Lego blocks snapping together Jukuan’s molecule grabs a desired compound without need of a catalyst and additional rinsing steps.

Matt Becker says the idea behind click chemistry is, "you want to attach molecules with no residuals and therefore you don’t have to purify it.”

Becker says growth factors that hasten the healing of nerves, bone, or damaged blood vessels; or drugs, or beneficial proteins can click onto the polymer bandage with one step.

“You basically take your slide, dip in water, shake it a little bit and use it.”

Customizable bandage for any tissue type

Becker imagines the new polymer bandage customized by surgeons who rebuild blood vessels or nerves, or even a part of an Army medic’s field kit -- one bandage treating multiple wounds. The University of Akron and the Austen Bioinnovation partners are eager to move forward.

He says the new polymer bandage will be tested in animals within the next three months, and "we’re already talking to companies about commercialization.”

For Darrell Reneker, cross-generational scientific discovery is a life-giving passion.

He says, “It’s just fun to work with people who share the interest and get caught up in the problem whatever age they are.”

Even after 60 years of working in labs, Reneker says there’s nowhere else he’d rather be. |