Reconnecting to severed sensory nerves

It was four years ago, early in Igor Spetic’s shift where he ran a forging hammer at a Cleveland plant when "somehow, my hand got between the dies.” And suddenly, his right hand was gone.

Now he’s is helping researchers at the Cleveland VA Medical Center learn how to replace some of what he’s lost.

Spetic explains that in this experiment, "I just feel a tingling at the base of my thumb.” Only, the thumb is not there.

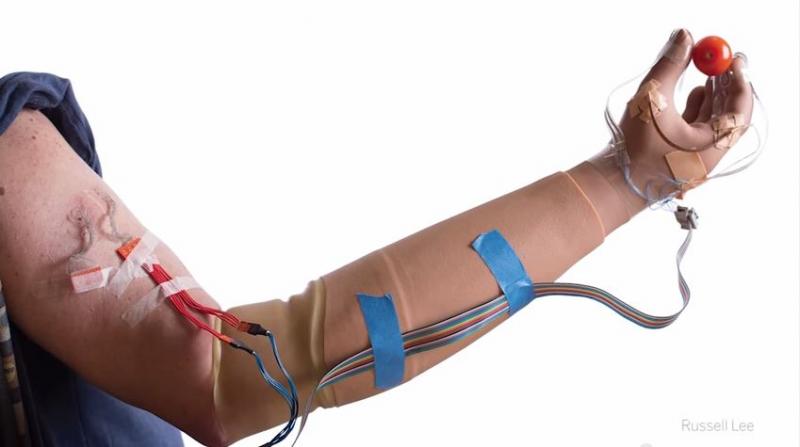

Spetic is feeling a computer-generated sensation fed into a tangle of wires protruding from his upper arm. Spetic is feeling a computer-generated sensation fed into a tangle of wires protruding from his upper arm.

Those wires run under his skin to three specially engineered electrodes that wrap around the nerves that used to receive sensations from his now absent hand.

Case Western Reserve University’s Dustin Tyler is head of the project.

He says the first time the stimulation to Spetic's nerve was turned on, "He got this funny look on his face and he goes, ‘That’s the tip of my thumb.’”

Engineering a neural interface

Tyler led the efforts to create these special electrodes, he calls them cuffs, that send electrical signals back up the sensory nerves in Spetic’s arm.

He says Spetic feels individual spots at 20 different places around his hand.

"He feels his thumb tip, the index tip, the middle finger tip, the palm, the wrist." Tyler explains, "He’ll feel it down the ulnar side, the pinky side of the hand, he’ll feel it on the back on his hand. So essentially everywhere on his hand, he can feel now.”

Tyler shows me the most advanced artificial hand from prosthetic manufacturer Ottobock. It's called the Michelangelo, a sculpted hand equipped with sophisticated robotics.

Tyler says soon prosthetic hands like the Michelangelo will not only be able to move, they’ll be able to feel. Sensors placed in the tips of the fingers and around the hand will be able to transmit pressure and perhaps, texture sensations.

Learning to speak the language of sensation

At the VA, Tyler’s team is learning how to alter the strength and pattern of electrical signals sent to the nerves to mimic real touch.

"We’re starting to talk the right language so the person feels what we want them to feel."

Tyler says the sensors are able to transmit specific sensations like sandpaper or Velcro "or just a constant pressure.”

No one really knew if this approach would work, but team member and Cleveland Clinic neuroscientist Paul Marasco says the brain is very good at adapting to new input, whether from a new touch experience or from artificial electrical signals.

“And so even when it was thought that people might not be able to feel touch any more," says Marasco, "they do, and they feel it very well.”

Marasco says another important part of restoring sensation to amputees is the emotional component of touch.

“We connect very well to people," he says. "We like to hold people’s hands; we like to touch things; we like to feel things.”

Saying goodbye to phantom pain

Another issue addressed by the sensation stimulation was Igor Spetic’s phantom pain, a chronic sensation he describes as feeling "like it was crushed in the vise 24/7.”

Dustin Tyler says alleviating that pain was an unexpected side-benefit of stimulating the nerves.

“By having the brain recognize, ‘Oh, there is a hand here again,’ he doesn’t have that pain any longer,” says Tyler. “By having the brain recognize, ‘Oh, there is a hand here again,’ he doesn’t have that pain any longer,” says Tyler.

At the VA lab, Spetic shows me how his mechanical hand moves. But it doesn't feel, a capability he’s helping the researchers make happen.

He looks forward to the time when he and other amputees can have a prosthetic limb that is not just a tool that's worn, but something that is "actually part of me again.”

Tyler feels that in the next five years his team will be able to create a prosthetic hand that can provide nearly 90 percent of movement and sensation. But he acknowledges a hand can’t be replaced.

He says the better goal is "to make them forget they lost one.”

Tyler is partnering with device-maker Medtronic to develop an implantable sensation stimulator with an anticipated $16 million in Department of Defense funding over the next five years. |