It’s a Friday night and the Akron-Canton Airport is just about deserted. Except for the vibrant cluster of reds and golds and excitement near the arrival gate.

"Oh my God. My daughter, my grandson.”

Lal and Indrawoti Rai and their very extended family are welcoming their daughter and grandson, who stayed behind when the rest of the family left Nepal to settle in Akron six years ago. Cell phones and Skype have kept them figuratively in touch. But, as Lal continues to hold the boy -- his son, Sudan, says it’s long been clear that can’t be enough.

“It’s been a long time. My dad always when he talked on the phone he’d start crying and it was very stressful. Now… yeah…it’s very exciting.”

Five hundred a month

Different versions of this story have been playing out just about every week as Akron has increasingly become home to thousands of Bhutanese refugees.

Their migration to Akron’s North Hill neighborhood actually began more than a century ago – and involves a people rooted in two countries.

From Nepal to Bhutan and back

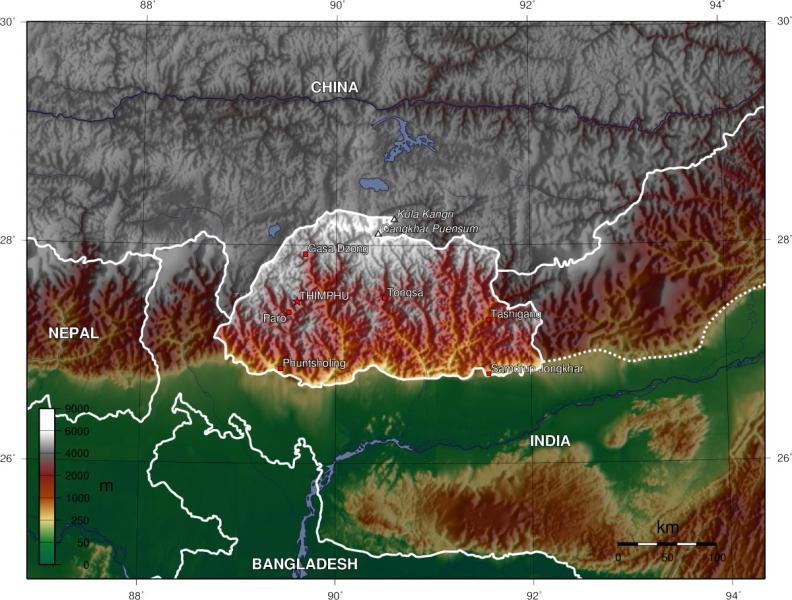

The tiny Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan – tucked between India and China -- invited Nepali families to farm the south of Bhutan. Separated by language, culture and in many cases religion, they ran afoul of the one-culture push by the Bhutanese government in the later 20th century. between India and China -- invited Nepali families to farm the south of Bhutan. Separated by language, culture and in many cases religion, they ran afoul of the one-culture push by the Bhutanese government in the later 20th century.

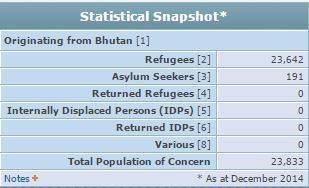

Stripped of farms and freedoms, more than 100,000 people ended up in the seven sprawling U.N. refugee camps in southeastern Nepal, where many remained for more than 20 years.

The 1951 Refugee Convention defines a refugee as someone who:

"owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion,

nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality, and is unable to, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country." |

Madhu Sharma, the immigration attorney with the International Institute of Akron, says as with many refugee stories, it’s a story of strength.

"We see them so often as victims, but they also are survivors. And I think that is what is so important to remember because survivors often have a lot to contribute to the community surrounding them."

In the beginning

Beginning with a Bush administration decision in 2006, the community that would surround most of them was the U.S.

At the time, there were only about 150 Bhutanese in the entire U.S.

Naresh Subba was one of them. He now runs a food market in North Hill with his brothers – a store that specializes in bags of rice the size of small children, exotic versions of melons, beans and eggplants, baskets of brilliantly colored peppers and a puffed-rice dish called “chatpatay” that can only be eaten with a bucket of water nearby. Naresh Subba was one of them. He now runs a food market in North Hill with his brothers – a store that specializes in bags of rice the size of small children, exotic versions of melons, beans and eggplants, baskets of brilliantly colored peppers and a puffed-rice dish called “chatpatay” that can only be eaten with a bucket of water nearby.

But back in 2002, after attending a university in Kathmandu on a camp scholarship, he headed to Kent State to get his doctorate in nuclear physics. And that indirectly opened the pipeline from Nepal to Northeast Ohio.

Subba notes that refugee resettlement efforts look for relatives in the new

countries. And "the definition of family in our culture and the definition of family in the U.S. is totally different of course. When I say family, I am thinking of not only my wife, my children, but I’m thinking of my mother, my brothers, my sisters and my in-laws and everyone included. Very extended. That is what we mean by family.”

So by that flexible definition of family, Naresh Subba ended up being a distant cousin to just about everybody.

It took more than that, of course.

Decades of resettlement

Another part of the pipeline is the nonprofit International Institute of Akron. For decades, it’s been housed in a warren of offices in Akron’s North Hill – blending with neighborhood originally settled by Italian immigrants.

The institute is charged with resettling, among others, people who meet the U.N. definition of a refugee – people persecuted because of their race, nationality, religion, political opinions or social groups.

The resettlement begins with background checks and other screening overseas -- a process that can take years. The resettlement begins with background checks and other screening overseas -- a process that can take years.

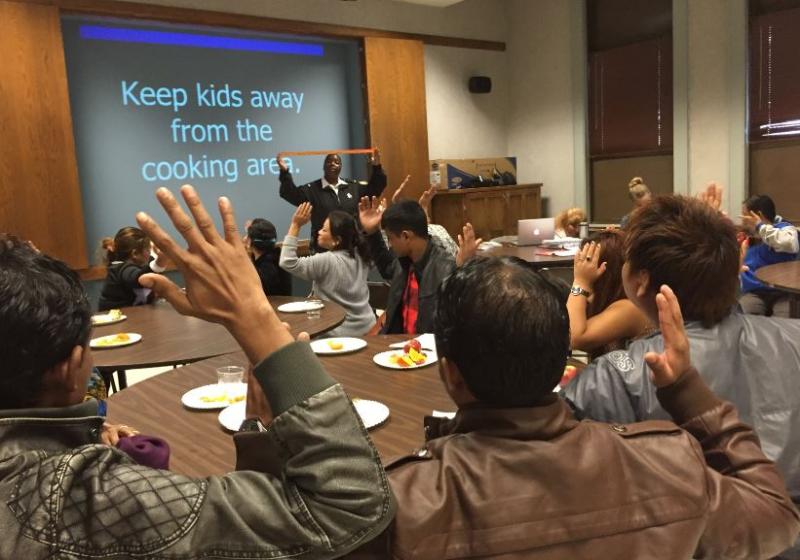

the refugees' arrival here triggers a 90-day march towards self-sufficiency, and that begins with a nearly week-long orientation. Mary Raitano, the institute's resettlement director begins with praise and caution.

“You are very brave for coming here. I am very impressed with all of you that you had the courage to come. But you’re going to have to continue to be brave and try new things. “You are very brave for coming here. I am very impressed with all of you that you had the courage to come. But you’re going to have to continue to be brave and try new things.

Through an interpreter, she's speaking to nearly three dozen people – all in the U.S. for less than 30 days – in the basement of the Blessed Trinity Catholic Church. The orientation teaches everything from how not to set the kitchen on fire to the best chances for getting a job.

Living out the dream, though the dreams vary

Nilam Ghimirey and her family have lived out plans well beyond self-sufficiency. She was the 2012 valedictorian at North High School, is an honors major at Kent State and plans to become a doctor. Nilam and her family arrived in Akron in 2009, early in the Bhutanese migration. She was inspired by her time in the camps. Nilam Ghimirey and her family have lived out plans well beyond self-sufficiency. She was the 2012 valedictorian at North High School, is an honors major at Kent State and plans to become a doctor. Nilam and her family arrived in Akron in 2009, early in the Bhutanese migration. She was inspired by her time in the camps.

The seven refugee camps in Nepal originally held more than 100,000 Bhutanese people. Five of the camps are now closed and the other two are slated to close within two years.

|

“When I was in camp, you didn’t dream for big things. But there were no doctors and you see all these diseases and people suffering.”

The newer arrivals have benefits the earlier settlers did not: An extended community.

But the newest-comers also face additional challenges -- ironically linked in part to the success of the resettlement. The last of the camps in Nepal are expected to close within two years. So those leaving now have been there longer, and are often poorer, less educated, older -- and scared.

Elaine Woloshyn, head of the International Institute, says her staff is cognizant of the evolving challenges. But one thought remains dominant.

“We are reuniting families.”

That’s family. By a lot of definitions.

|